Credit Risk Shifts to LGFVs

How Beijing manages this stress will be a crucible for commitments to financial reform and the deleveraging campaign.

Local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) have been central to the credit-intensive growth model China has followed since 2009, but new regulations have restricted local government support for these entities this year. Though a recent relaxation of funding conditions signaled by the State Council may stabilize infrastructure investment and improve LGFV access to financing at the margin, the headwinds facing local government-linked firms are significant.

Outstanding LGFV debt levels are over twice as large as government data would imply, based on a comprehensive examination of public records of bond filings. Interest payments on LGFV debt consume significant proportions of some provinces’ overall new credit. We expect the first-ever LGFV bond defaults to emerge soon, which could test market expectations of government support in many other asset classes as well. How Beijing manages this stress will be a crucible for commitments to financial reform and the deleveraging campaign.

Local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) have been the primary channel through which authorities in China have delivered new infrastructure investment and generated growth over the last decade. But in the first half of 2018, Chinese authorities took decisive steps to restrict government guarantees of these vehicles, the collateral they can use, and the scope of LGFV business activities. These policies come amidst regulatory tightening elsewhere in the financial system; funding sources for trust companies and other non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), which are important lenders to LGFVs, are drying up. Moreover, local governments are increasingly under strain, in part because they are being forced to assume and repay implicit debts from LGFVs and other local government state-controlled entities.

We expect to see more credit stress and actual defaults on bonds issued by these local government-backed firms for the rest of the year, even though recent policy guidance from the State Council for banks to maintain financing to infrastructure projects in progress will probably marginally improve LGFV financing. Defaults on bonds issued by LGFVs would be a watershed event, weakening the credibility of the long-held assumption that firms with state backing would never ultimately default because support would always be forthcoming. While state-owned enterprises have defaulted in the bond market already, LGFVs have not.

Widespread implicit and explicit government guarantees have limited the effective pricing of capital throughout the Chinese financial system, as credit risk in the corporate bond market was generally priced based on the nature of the government guarantor, rather than the underlying financial performance of the issuer. The strength of these implicit guarantees and the assumption of government intervention in cases of widespread financial stress has therefore preempted the need for institutional methods of managing distressed, quasi-governmental debt, meaning that even a small number of defaults among LGFV bonds could cause significant turbulence in China’s debt markets.

Moreover, the debt burden of LGFVs is likely larger than what is being declared publicly in government audits. An analysis of financial data provided by LGFVs within their filings tied to bond issuance points to an estimated 41.8 trillion yuan in total interest-bearing debt as of July 2018, or around 51% of China’s 2017 GDP. This compares to only 16.5 trillion yuan in explicit local government debt acknowledged by the Ministry of Finance as of the end of 2017. Moreover, LGFV borrowing is classified as corporate debt, and carries higher interest rates than government debt (which explains the original Ministry of Finance plan to refinance a portion of it). As a result, many provinces are using more and more new credit simply to manage the interest burden of LGFV debt.

Compounding these financial stresses is the unequal distribution of credit growth across provinces under Beijing’s deleveraging program. Because some provinces—mainly those in China’s interior—relied more heavily upon informal financing channels in the past, they have been hit disproportionately by the funding squeeze on NBFIs. Placing these trends together—rising LGFV debt and an unequal distribution of provincial credit—reveals that certain provinces are facing significant financial stress from LGFV debt, and are likely to require additional central government assistance soon.

A Heavy Debt Burden for Many Provinces, Especially Tianjin

LGFVs have been a key driver of infrastructure investment and growth at the local government level for the past decade, even beyond the post-crisis stimulus program for which they were originally designed. Localities were forbidden from borrowing or running fiscal deficits, and in response to these pressures, Beijing allowed localities to create off-balance sheet entities known as local government financing vehicles which could borrow without a revision of the underlying budget law, functioning essentially as local state-owned enterprises, but with clean balance sheets as they were newly created.

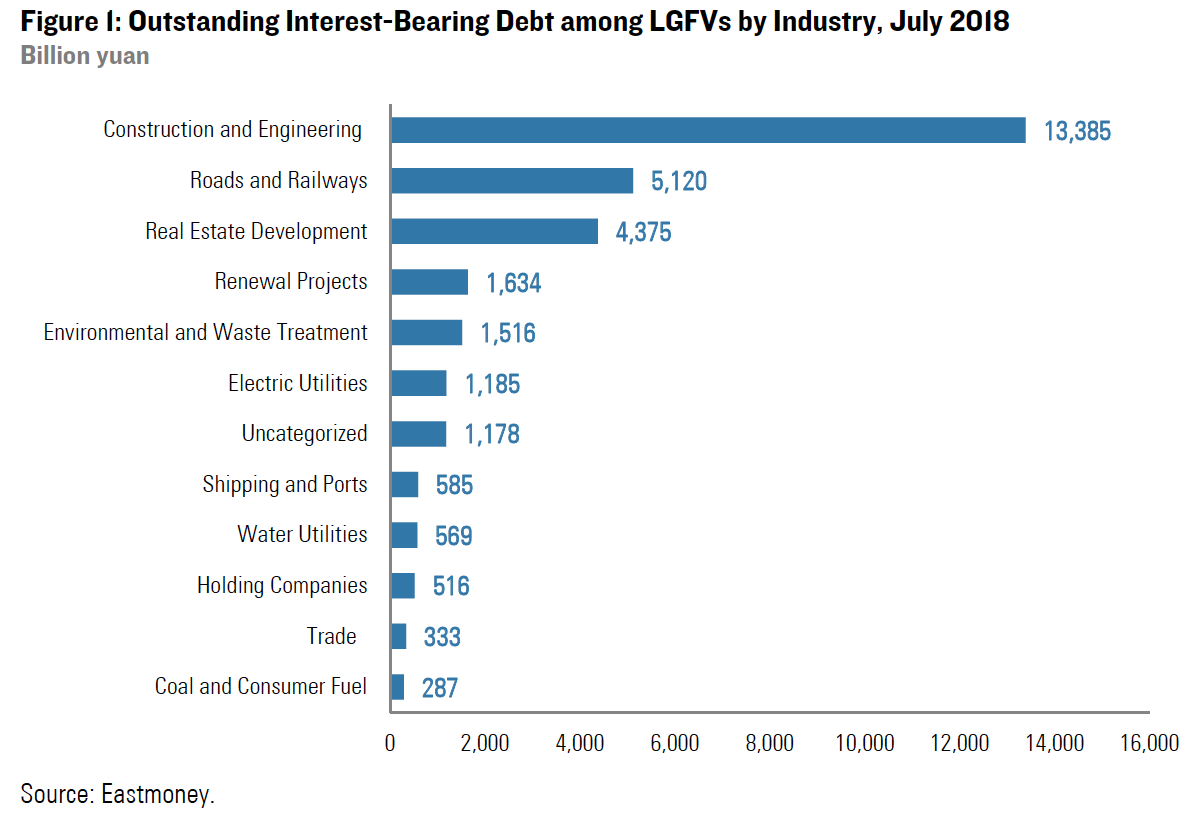

Local governments and their banks have distributed or otherwise guided enormous volumes of credit through LGFVs into local government projects. Most of these projects involve infrastructure or the property market, as Figure 1 illustrates. The top three categories reflect more than half of our total estimate of national outstanding LGFV debt. However, because these projects typically see low operating cash flows, banks must carry the burden of refinancing those obligations for localities.

To estimate the overall volume of LGFV debt we relied on public financial statements for LGFV bond offerings available on EastMoney, which is a China-focused information service provider that classifies LGFVs as firms whose shareholder is a local government and whose business includes local infrastructure and public utilities. LGFVs list bonds on different markets and then are required to file annual reports on these exchanges with financial data. Within these annual reports, LGFVs list their total outstanding debt in both interest and non-interest-bearing terms.

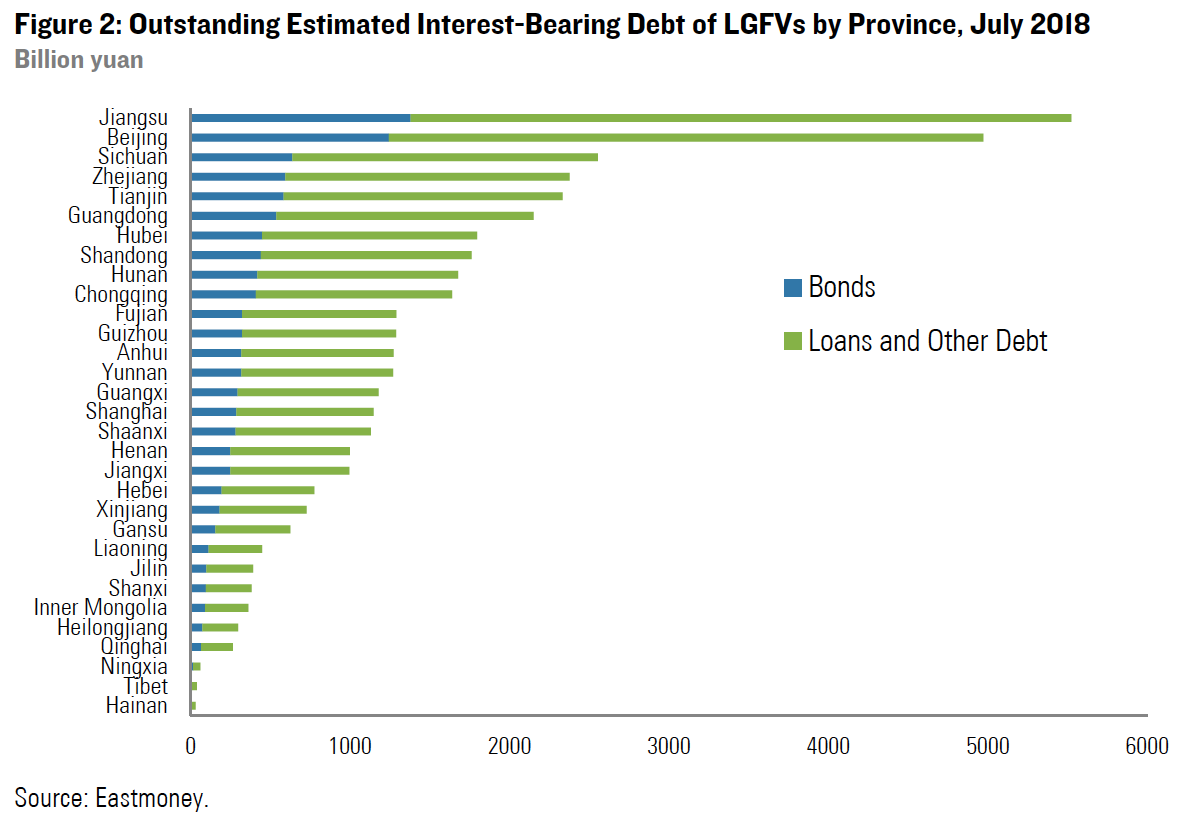

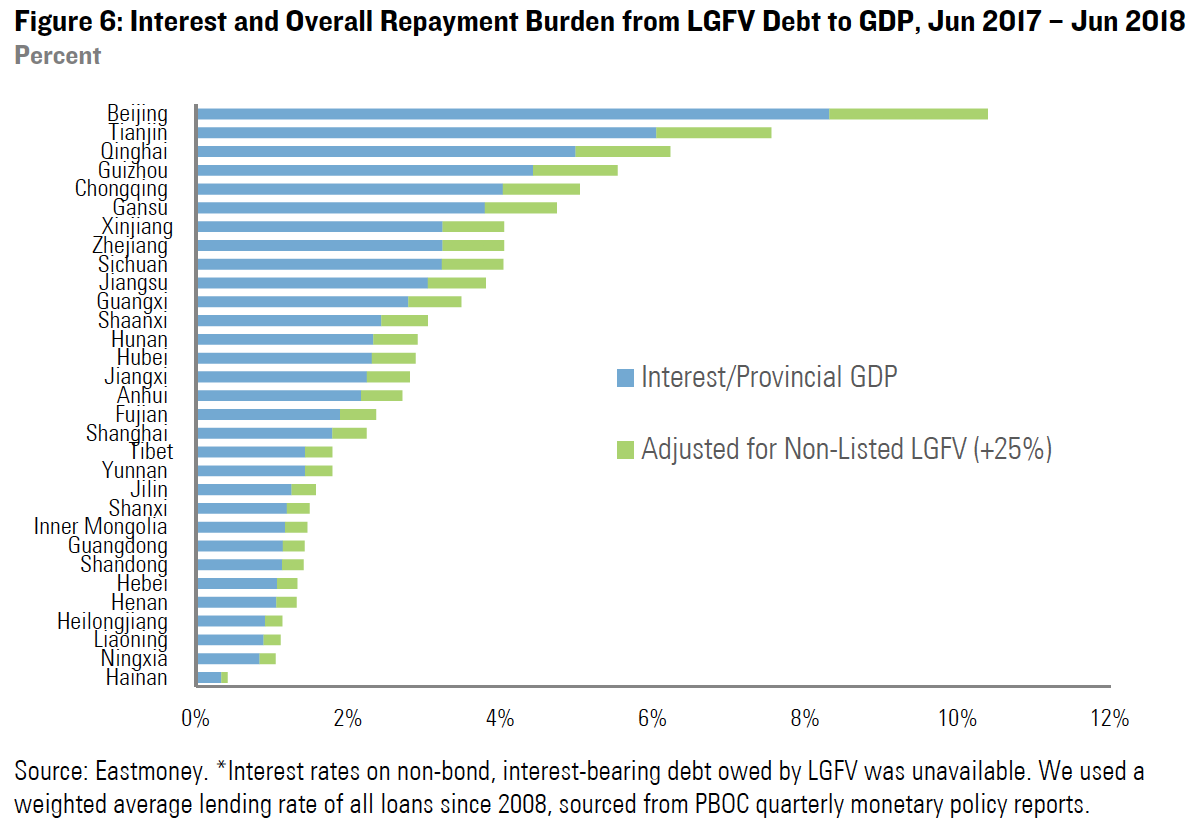

For the figures below, however, we limit our calculations to interest-bearing debt, applying a weighted average interest rate of bonds as issued and average PBOC lending rates over the past 10 years, since most LGFV borrowing is classified as corporate debt. The weighted interest rate is sourced from the PBOC’s own quarterly monetary policy reports, with an average rate used from 2009 to 2018. To account for LGFVs which do not have any bonds listed, we adopt estimates from the work of Bai, Hsieh, and Song, who have estimated that debt accrued by non-issuing firms amounts to about 25% of debt listed on platforms.[1] The data available on these financial platforms is a relatively new resource, and the totals are much higher than official figures for local government debt. Markets are therefore likely underestimating the risk associated with LGFV debt at present. Figure 2 shows estimated interest-bearing debt, in bonds and loans, by province.

We estimate that total interest-bearing debt among these vehicles (including the 25% adjustment mentioned above) is 41.8 trillion yuan as of July 2018, which is 46.8% of combined provincial GDP over the past four quarters. The annual interest burden on this debt totaled an estimated 2.1 trillion yuan, or 2.32% of the last year’s output, but the total repayment burden doubles to 4.65% of GDP when accounting for non-issuing LGFVs and maturing bonds. Filings also cite non-interest-bearing debt at an additional 17.1 trillion yuan, a large sum that will only increase the overall repayment burden of these vehicles.

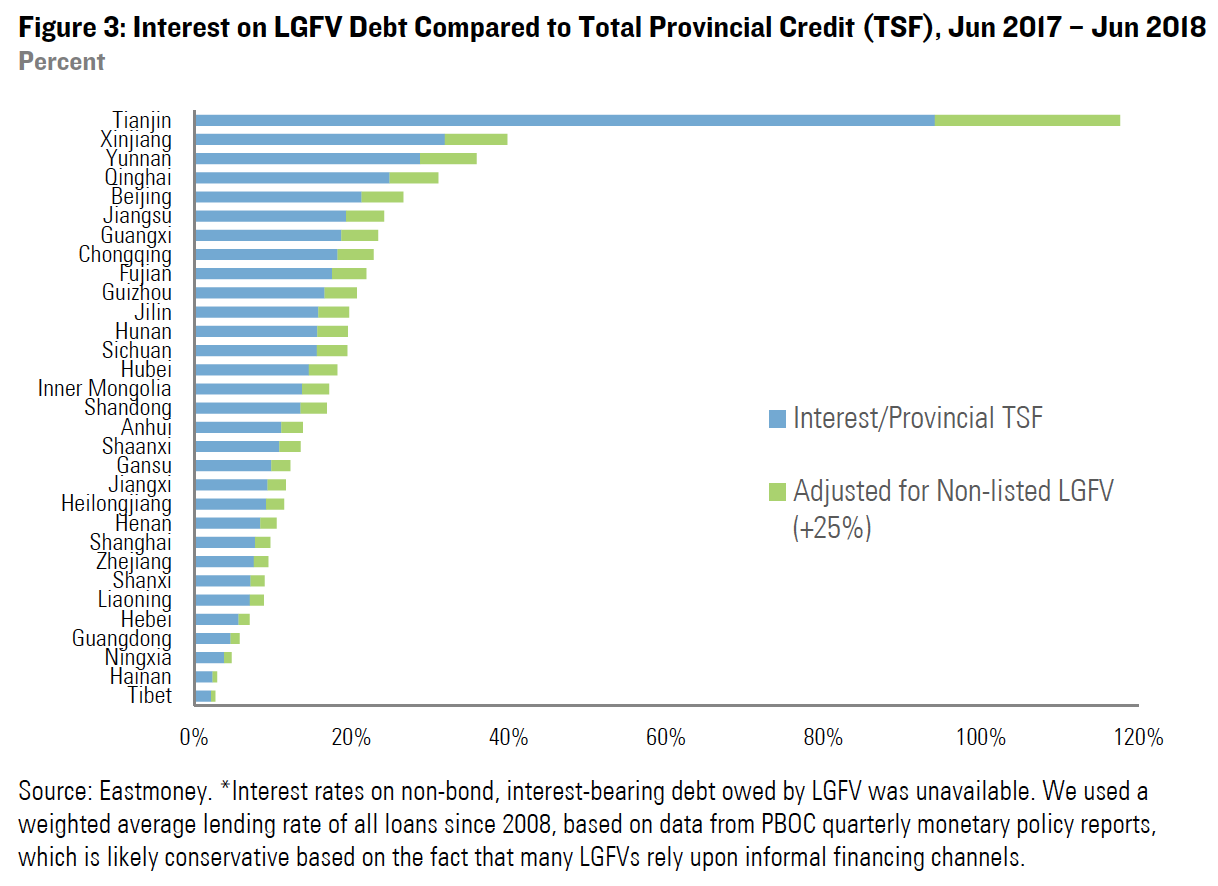

Figure 3 clearly highlights the extent to which the need to service outstanding LGFV debt is absorbing new funding across provinces. Annual interest totaled over 20% of total new credit (TSF) in eleven provinces over the previous four quarters, not even accounting for the need to roll over a large portion of maturing LGFV bonds, which totaled 1.56 trillion yuan over the past year. The worst-off provinces are concentrated in less developed regions in the northeast and southwest, with Tianjin as a notable concern. Interest on debt accrued by Tianjin LGFVs is over 100% of the new credit extended in the province over the past four quarters, meaning that every yuan of new credit in Tianjin is repaying interest on LGFV debt. This is primarily because TSF growth in Tianjin is rising at only 2.5% y/y, according to PBOC provincial credit data released early in August.

The reason to be increasingly concerned about the possibility of LGFV bond defaults in particular is the unequal distribution of this annual interest burden across provinces. Some provinces relied upon LGFVs far more extensively than others, particularly those in China’s interior. Corporate bond defaults this year have resulted from weak credit availability, rather than the underlying financial performances of the firms involved. And these vulnerable regions are seeing particularly slow credit growth in 2018. There is a significant overlap among provinces with higher LGFV interest-to-TSF ratios and those which experienced the highest levels of defaults and risk warnings issued within China’s bond markets so far this year (See May 29, “A New Era in Credit Risk”).

Higher provincial debt burdens also correspond to anecdotes of LGFV financing stress. Yunnan State-Owned Capital Operation Co., for example, missed payments worth almost 1 billion yuan in January this year. The LGFV financing platform Tianjin Municipal Development failed to repay half of a 500 million yuan trust loan that matured in late April. Even if credit growth stabilizes on a national level, there are likely to still be regional governments facing significant financial stress.

We expect to see further signs of stress in the top provinces on this chart later this year, but how authorities will handle credit these events is yet unclear. The first LGFV bond default may not prompt an immediate response, but subsequent defaults may trigger some sort of government action to attempt to stabilize the markets. Given the extremely high ratio of interest to credit availability, there should have already been a multitude of defaults among these firms, at least in Tianjin if not elsewhere.

Indeed, there has not been a single instance of default on an LGFV bond so far, despite 7 trillion yuan in outstanding notes; most reported payment difficulties have been on trust or asset management products. It is likely that de facto defaults on other obligations have occurred, but that the companies and local authorities have attempted to find third-party guarantors or lobby the central government for support to avoid explicit bond defaults. It will be increasingly difficult to conceal this stress as repayment difficulties pass through financial institutions, which own LGFV debt, and limit the credit they can offer to other corporates and households.

Refinancing Difficulties Rising

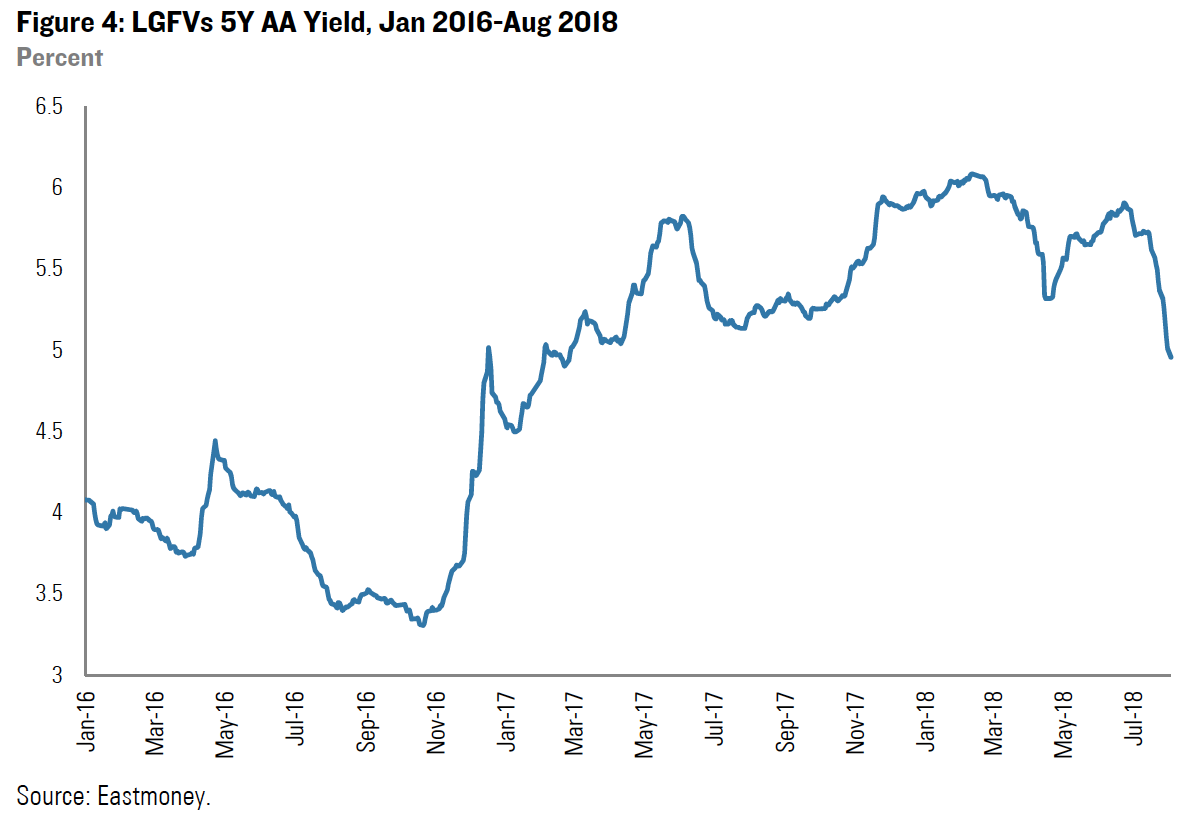

As Beijing’s deleveraging program has progressed, banks have been pulling back funding from NBFIs, which have been key lenders to LGFVs and buyers of LGFV bonds as they search for the higher yields these securities offer. As a result, LGFV bond yields have risen around 200 bps over the course of Beijing’s deleveraging program. They have rallied, however, after the PBOC recently offered medium-term funding for banks willing to purchase lower-rated bonds (See July 19, “The PBOC’s Visible Hand”).

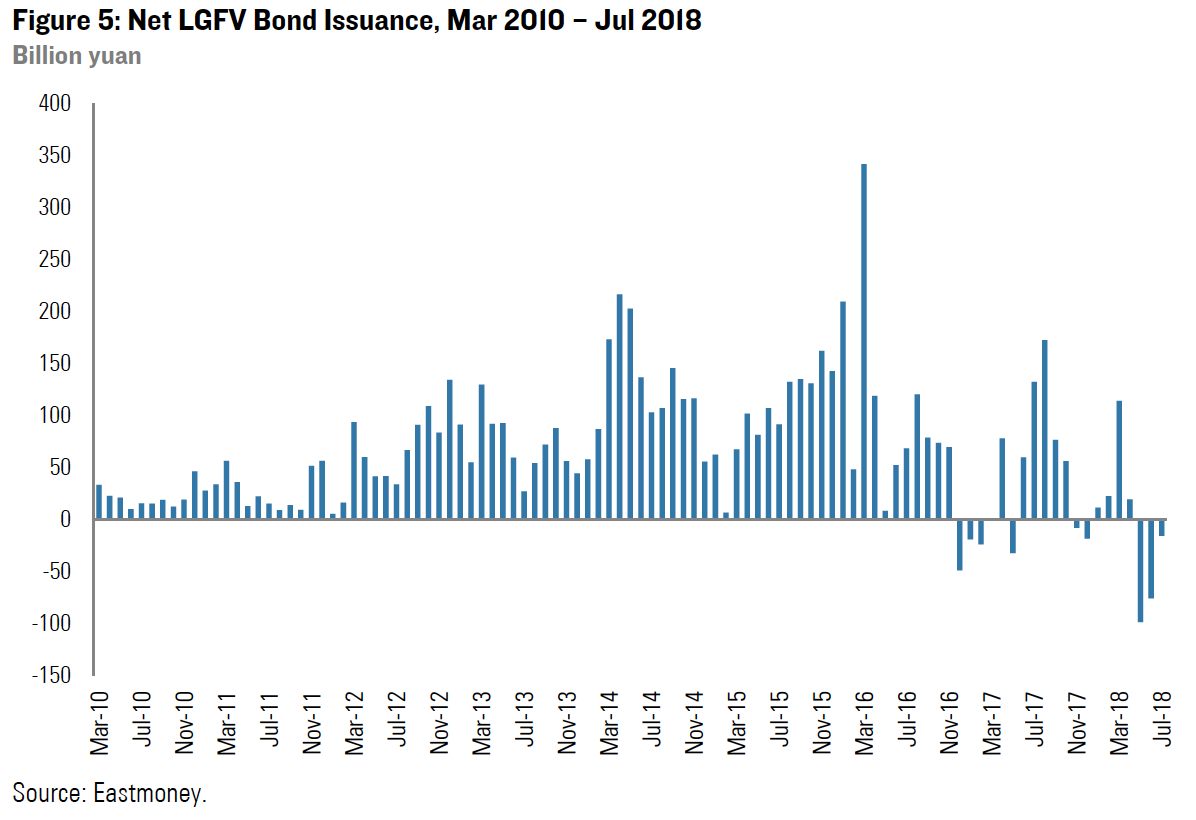

While funding costs have eased in recent weeks, higher rates and regulatory restrictions have significantly reduced LGFVs’ ability to acquire funding in the bond market over the past 18 months (See Figure 5). There are currently about 7 trillion yuan in outstanding LGFV bonds, according to Eastmoney data. And so far this year, maturing bonds have outpaced new issuance. In 1H 2017, total net LGFV bond issuance was 195 billion yuan, a record low, and issuance in 1H 2018 actually contracted by about 22 billion yuan.

Looking at bond issuance by province, less developed provinces that have nevertheless disproportionately relied on LGFVs, like Inner Mongolia, Guizhou, Chongqing, and Yunnan, have issued very few bonds in net terms this year. The picture becomes more worrisome when comparing this marginal issuance to the interest burden on existing bonds. Tianjin, for example, only issued a net 10.9 billion yuan worth of bonds in 1H; we estimate the province’s 6-month interest burden, on bonds only, to be 13.3 billion yuan.

There will be 672 billion yuan in LGFV bonds maturing over the remainder of 2018. Given that several provinces are unable to even issue enough bonds to keep servicing existing debt, it is highly unlikely they will be able to repay or roll over the principal coming due, at least through the corporate bond market.

The Crying Baby Gets the Milk, But From Whom?

As mentioned previously, new restrictions limit the ability of local governments to guarantee LGFV debt and these vehicles are forbidden from using public assets as collateral. But even if localities were allowed to support LGFVs directly through fiscal outlays, it is doubtful that they would be able to do so without receiving central government support themselves. Indeed, the financing restrictions from new asset management rules and the ongoing implicit local government debt audit are aimed at placing official limits on the degree to which localities are liable for LGFV borrowing, in part to limit the growth in already enormous levels of local government debt (See July 30, “The PBOC-MOF Battle Over Local Government Debt”.)

Figure 6 compares the outstanding LGFV debt burden to provincial GDP, which is a rough proxy of the extent to which provinces have relied on these vehicles to generate growth over the past decade. More importantly, it approximates the ability of provincial economies to withstand the burden of LGFV debt. Interestingly, Beijing comes out on top, likely reflecting that many LGFVs that do not operate in Beijing report as being based there, meaning that the city itself is probably not responsible for this debt. The debt burden is clearly outsized in less developed provinces of Guizhou, Qinghai, Gansu, and Xinjiang. It is remarkable that interest payments alone, not even accounting for the principal of existing debt, amount to over 4% of GDP in nine provinces.

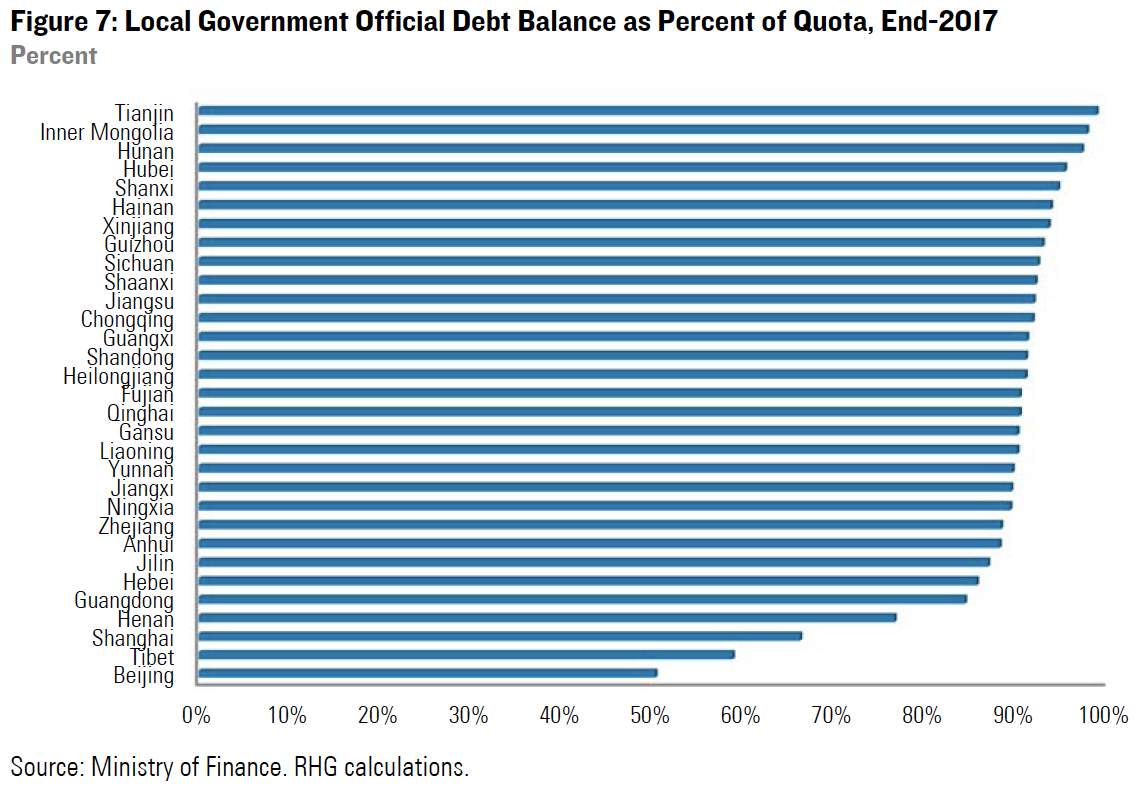

Moreover, many of these provinces have already borrowed at official levels close to their provincial debt quotas from the Ministry of Finance. This means that official local government bonds are unlikely to be available tools to refinance LGFV debt, for most of the most heavily indebted provinces. These quotas can be lifted, but the central government will need to do so affirmatively, in contrast with the current direction of policy to encourage localities to pay down implicit debt. Some central government assistance in the form of fiscalization or emergency liquidity will probably be necessary.

Separating the Sheep from the Goats

In the near term, Beijing is worried about financial contagion causing investors to sell or shy away from new purchases of LGFV debt. To address this, the State Council recently emphasized that financial institutions should meet “reasonable” funding demand from LGFV projects currently under construction to avoid them being abandoned, which would generate immediate fiscal costs for localities. The PBOC at the end of last month released one of the largest injections of medium-term lending (MLF) in the facility’s history, over 500 billion yuan, targeted at improving liquidity within the lower-rated corporate bond market. Markets have responded to this PBOC move, buying bonds of LGFVs that have operating cash flows, such as toll roads. Other LGFVs without such cash flows are still likely to face refinancing difficulties.

There has been conjecture among analysts concerning whether these moves indicate that authorities are relapsing into the old model of stimulating credit and investment-fueled growth. A return to expedited investment through these vehicles would indeed be a blow to macroeconomic restructuring, not just the deleveraging campaign. But Beijing’s overarching goal in implementing restrictions has been to separate local government revenue and funding channels from those of local government financing vehicles, not to deprive all LGFVs or local governments of funding. Overall, regulatory tightening persists consistent with the deleveraging campaign, and continues to limit credit growth. The PBOC’s recent support for the corporate bond market also coincided with a State Council announcement precluding the possibility of “opening the flood gates” of fiscal spending in a fashion similar to the 2009 stimulus.

[1] Bai, Hsieh, and Song, “The Long Shadow of Fiscal Expansion.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 22801 (2016).