Berlin and Beijing: German China Policy After Merkel

German Chancellor Angela Merkel will step aside later this year after 16 years in power, opening the door to what could be a shift in Berlin's policy towards China

The German election on September 26 has significant implications for Berlin’s policy towards Beijing and the broader international effort to address the geopolitical challenges presented by China’s rise. Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose pro-engagement policy towards China has shaped Europe’s approach for more than a decade and a half, will step aside, opening the door to what could be a shift in Germany’s stance. While we do not expect radical change in how Germany approaches the relationship with its biggest trading partner, we consider a meaningful evolution towards a firmer line likely. How significant this shift turns out to be will depend in part on the election result, the coalition government that emerges and who ends up running it.

Although geopolitics has played a secondary role in the campaign so far, and German voters are more preoccupied with the pandemic, climate change and domestic economic matters, the election is being watched closely in Beijing and Washington. Both understand the pivotal role that Germany plays in the relationship that advanced economies have with China — on issues ranging from human rights and climate to trade and technology. In this note, we sketch out the different election scenarios, their implications for Berlin’s policy towards China, and what to look out for under a new German government

Merkel’s legacy

No politician has had a greater influence on Europe’s approach to China in the 21st century than German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who will step down later this year (or early next) after 16 years in power. Merkel presided over a period of rampant German investment and trade with China, and closer political ties with Beijing, establishing a “comprehensive strategic partnership” between the two countries and introducing annual meetings of top cabinet officials. At the European level, she put China at the heart of her agenda when Germany held the presidency of the European Council in the second half of 2020, clinching a political agreement with Beijing on the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) last December. When tit-for-tat sanctions in March doomed ratification of that agreement, Merkel went out of her way to ensure that relations with Beijing remained on track, holding a series of damage-control videoconferences with China’s President Xi Jinping.

Crucially, she has been instrumental in carving out a distinct path for Europe at a time of escalating geopolitical competition between the United States and China, seeking to strike a balanced approach and not siding too overtly with Washington in its confrontation with Beijing. Together with French President Emmanuel Macron, she has led the push for a more independent, sovereign Europe – an approach that was borne of Europe’s strained ties with the Trump administration, but which has continued under Biden. It is important to note that Merkel has not stood in the way of the European Union’s years-long push to develop an arsenal of new rules and regulations to push back against China, mainly in the economic sphere. But she has ensured that this technocratic response, aimed at creating a level playing field in the relationship, has not turned into a deeper anti-China backlash. This should not be confused with a policy of “equidistance” between the US and China. She and other members of her government have made clear that Berlin considers its relationship with Washington to be closer because of historical ties, and the democratic political system and values that the two countries share. But as tensions between Washington and Beijing have escalated in recent years, Merkel has tried to play a moderating role in the conflict, warning against the isolation or containment of China, and pushing back against the idea of a broader economic decoupling which was seen as counter to German interests.

While it would be wrong to expect a revolution in Germany’s approach to China after Merkel, we expect the shift towards a harder line in Berlin and Brussels that has been underway for several years to continue and possibly accelerate.

Changing of the guard

Merkel’s departure from the political stage raises questions about whether a new government could adopt a different approach. Views on China have hardened across the leading German political parties, the broader public, and parts of German industry in recent years. Some politicians, including members of Merkel’s conservative party, are calling for a reset that would give human rights, democratic values and national security concerns greater weight, and prioritize closer coordination of China policy, both within Europe and with allies like the United States and Japan. The Biden administration has spent the past six months trying to repair the damage that Donald Trump’s presidency did to the transatlantic relationship and pushing Europe to coordinate more closely on China. This process is already underway, as the G7, NATO and EU-US summits in June illustrated. But the departure of Merkel could accelerate this shift, leading not only to a change in tone, but a more open embrace of cooperation at the international level.

While it would be wrong to expect a revolution in Germany’s approach after Merkel, we expect the shift towards a harder line in Berlin and Brussels that has been underway for several years (at times in spite of Merkel) to continue and possibly accelerate. What is at stake in the looming election is not the direction of German policy towards China but the pace at which this hardening evolves. In the near-term, a new government will face decisions on Huawei’s role in the German 5G network and how to navigate the Winter Olympics in Beijing in 2022. In the years ahead it will need to wrestle with questions around its economic relationship with China – from supply chain security and technology exports to the role of German firms in the Chinese market – and how to position itself on Taiwan. Where Berlin comes down on these issues will depend on the makeup of the next government and the person who replaces Merkel as chancellor. But it will also depend on China’s own behavior on a range of issues, from human rights and climate to security and economic matters.

It is unlikely that we will know on election night what government will emerge and who the next chancellor of Germany will be. Indeed, this may not become clear until late 2021, or even early 2022.

Coalition scenarios

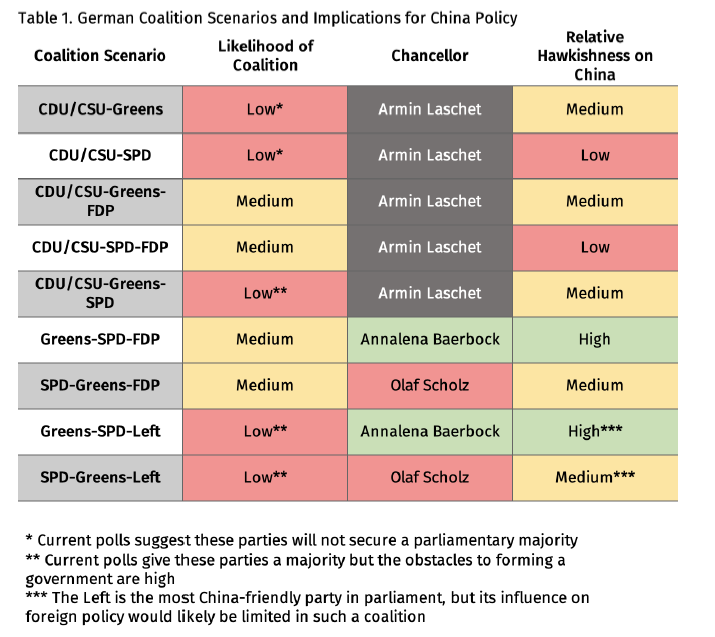

With roughly a month to go until the German election, there is a high degree of uncertainty about what the next government will look like and who will lead it. Polls suggest that there are as many as nine possible coalition scenarios (see Table 1), and that each of the three leading party groupings – Merkel’s conservative Christian Democratic Union and its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU), the environmentalist Greens, and the center-left Social Democrats (SPD) – could lay claim to the Chancellery. Under the four most likely coalition scenarios, the government would include two of these party blocs as well as the Free Democrats (FDP), a liberal party (in the European sense). This means that the formation of a coalition will be akin to three-dimensional chess – highly complex and time consuming. It is unlikely that we will know on election night what government will emerge and who the next chancellor of Germany will be. Indeed, this may not become clear until late 2021, or even early 2022.

Green long shot

In assessing the potential for shifts in China policy, a crucial question will be whether the Greens are part of the next government, and more importantly, whether they are leading it. While all the parties listed above, except the far-left Left party, have adopted a tougher line on China in recent years, the Greens, and their chancellor candidate Annalena Baerbock, have been the most vocal in calling for a break from the Merkel era. If Baerbock emerges as chancellor atop a so-called “Ampel” coalition with the SPD and FDP – a scenario that seems less likely given the SPD’s recent surge above the Greens in some polls – then a harder German line on China, in both tone and substance, is likely from day one.

If the Greens are junior partner in a coalition led by the CDU/CSU or SPD, then the party’s influence over China policy would be diminished, but it would still have a voice at the cabinet table and could work with the more hawkish elements within those parties (and the FDP) to push for a harder line. If the Greens are not part of the next government, it is less likely that Germany will see a pronounced shift in its approach to China. In their statements on the campaign trail, CDU/CSU candidate Armin Laschet and SPD candidate Olaf Scholz have both played down the need for major changes in Germany’s foreign policy approach, cautioning against confrontation with (or economic decoupling from) China. Still, they would face the same pressures – at home, in Europe, and from allies like the US – that Merkel has in recent years. As her setbacks this year on the CAI and on German 5G policy suggest, these pressures are likely to prove difficult for a new chancellor to resist – particularly one who, at the outset at least, will not have the stature or international credibility that Merkel built up over many years. Barring a shift in China’s own policies – on issues like human rights, climate, Taiwan, and the treatment of foreign firms – a gradual hardening of Germany’s line may be inevitable, although clear differences with the US approach will remain.

What to watch

As explained above, it is likely to take months for a new German government to come together. Once it does, political attention in Europe is likely to pivot rapidly to the French election in April 2022. Only after the dust has settled on both votes may a serious debate on Europe’s geopolitical positioning be possible (though such a debate is not inevitable). Below, we lay out five areas that we will be looking at in the post-election period in order to assess prospects for a shift in Germany’s and Europe’s positioning on China.

- A renewed push for EU unity on China: Under Merkel, Germany has often been accused of pursuing its own interests with China at the expense of a broader European approach. All of the mainstream parties say in their election programs that they plan to prioritize a more unified European position. Any new government will face challenges in delivering on this promise due to divisions among the EU’s 27 member states. But more unity will only be possible if Berlin leads the way and shows a readiness to make sacrifices.

- A whole of government approach: Under Merkel, the German government began holding regular inter-ministerial meetings on China, but these were mainly talking shops. The Greens have talked for years about pursuing a more joined up approach and CDU/CSU candidate Armin Laschet has backed the idea of a national security council to coordinate foreign policy. Breaking down the siloes and rivalries between ministries that are often led by politicians of different parties should be a priority of the new government.

- From climate cooperation to friction: The climate challenge is often held up as an issue where close cooperation with China is indispensable. But if Beijing continues to build and finance polluting coal-fired power plants and fails to deliver a roadmap for achieving its ambitious CO2 reduction targets, climate could become an increasing source of friction with Germany – especially in a government that includes the Greens. Watch for whether China is prepared to offer more in the run-up to the COP26 climate summit in November.

- Doing business with China: For decades, German governments have clung to the concept of “Wandel durch Handel” – the notion that closer economic ties would lead to political opening in Beijing. China’s evolution under Xi Jinping has rendered this idea obsolete but under Merkel there has been little room for debate about what comes next. A handful of large German companies, notably the big carmakers, are heavily invested in the Chinese market, and this dependence has shaped policy in the Merkel era. But the growing hand of the Chinese state in the economy, its escalating crackdown on private business and its push to localize supply chains pose a growing risk to German business interests there. At the same time, human rights and questions of national security have become part of the debate over doing business with China. A new government should create the room for a fact-based examination and redefinition of German economic interests in relation to China. Merkel’s departure makes this possible. But it is unclear whether a new government will be willing to poke this hornet’s nest.

- Taiwan: Following Beijing’s crackdown in Hong Kong, concerns have been growing in Berlin about an escalation of the situation in Taiwan. Members of the Greens and FDP have been pushing for clearer positioning from Germany on the question, with the FDP removing a line from its party program that voiced support for a “One China policy”. At a time when the US, Japan and EU countries like Lithuania are becoming more outspoken on one of Beijing’s reddest of red lines, a new German government needs to assess whether a change of tack is needed.

Conclusions

On September 26, German voters will go to the polls to elect a new government which, for the first time in 16 years, will not be led by Angela Merkel. More than any other European leader in the 21st century, Merkel has shaped the bloc’s approach to China, prioritizing engagement with Beijing and the interests of large German companies, while pushing back against US efforts to isolate, contain and decouple from China. Her departure opens the door to change in Germany’s and Europe’s approach to Beijing. While we do not expect a radical shift, we do expect a harder German line to emerge with Merkel out of the picture. The makeup of the next government will be crucial in this regard. A German government led by the Greens could mean a change in tone and substance on China from day one. The more likely scenario is a three-way coalition that includes but is not led by the Greens. Regardless of the outcome, a new German government – and chancellor – will face pressures at home, in Europe and from allies like the US to further adapt its approach to new geopolitical realities in the years ahead.